THE AFRICAN COURT ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES RIGHTS: STRUCTURAL AND INSTITUTIONAL STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES AFFECTING ITS EFFECTIVENESS

PRESENTATION BY

THE HONORABLE JUSTICE GERARD NIYUNGEKO,

PRESIDENT OF THE COURT

DURING THE ROUNDTABLE ON STRATEGIES TO STRENGTHEN HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTION IN AFRICA

20 OCTOBER 2011

MOMBASA, KENYA

I. INTRODUCTORY OVERVIEW OF THE AFRICAN COURT ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Charter) is the main African human rights instrument setting out the rights and duties relating to human and peoples’ rights in African Union Member States. And within the broad outlines of that Charter, the African Union has been able to put in place an African Human Rights structural framework which encompasses among others, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Commission), the African Committee on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Court). However, among all these institutions, only the Court has the power to render binding and enforceable judicial decisions.

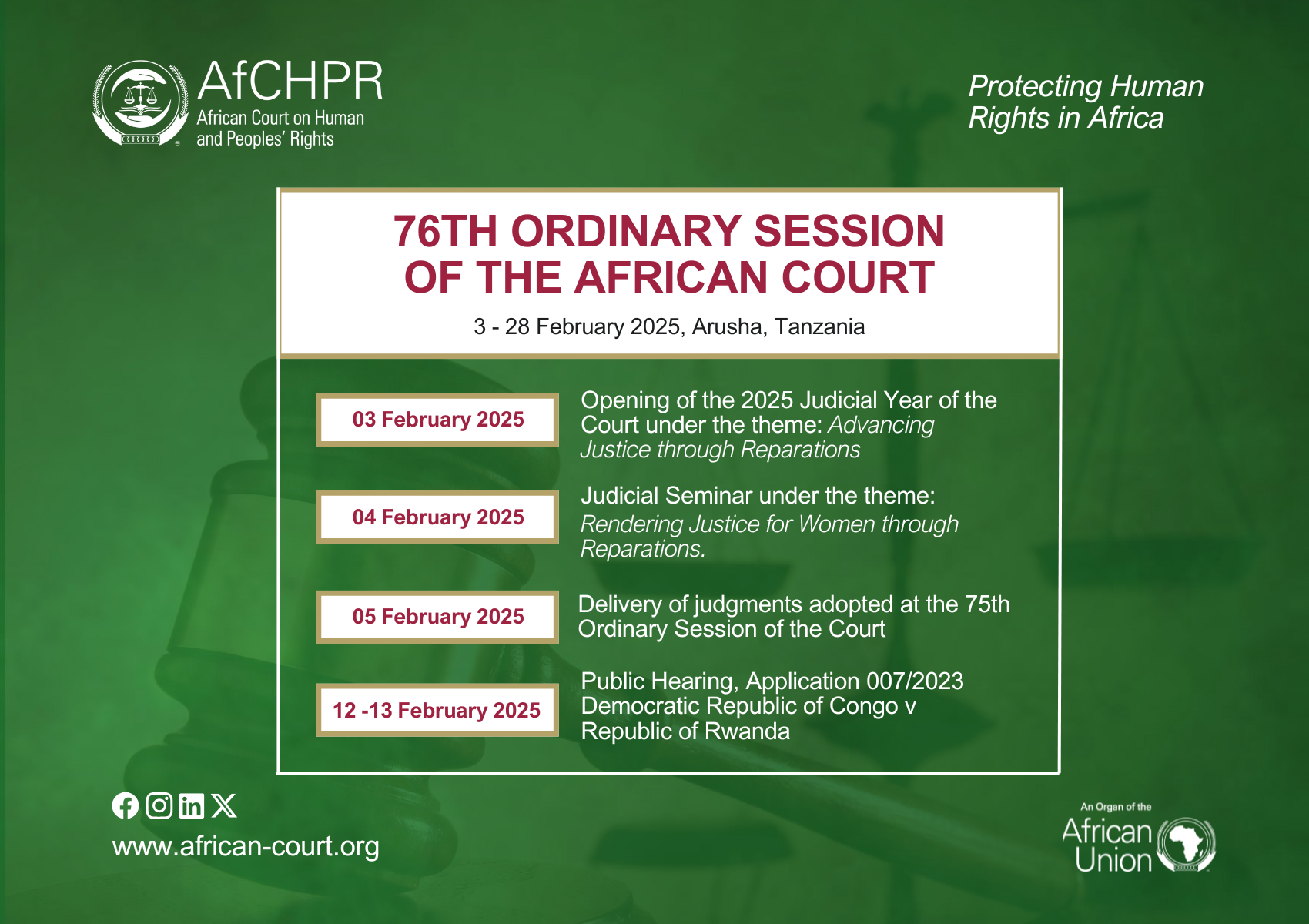

1. Establishment

It will be recalled that the Charter established the Commission, which has been in existence since 1987, as a quasi-judicial body that monitors the implementation of the Charter. In 1998, the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union/AU) adopted the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the Protocol). This Protocol entered into force on 25 January 2004, paving the way for the operationalization of the Court, with the election of the first Judges of the Court being held in 2006.

The Court has its seat in Arusha, Tanzania, where it relocated from Addis Ababa in August 2007.

2. Composition

The Court is composed of eleven (11) Judges, nationals of States parties to the Protocol, elected in an individual capacity. No two Judges are nationals of the same state. The Judges are elected by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union (AU) as far as is possible, on the basis of the geographic and legal systems of Africa as well as gender. They may be reelected only once. All Judges, except the President of the Court, perform their functions on a part-time basis.

3. Mandate

The Court’s mission is to complement the protective mandate of the Commission.

4. The role of the Court in contentious matters

4.1 Access to the Court

Article 5 entitles the following entities to submit cases to the Court:-

- The Commission

- States parties to the Court’s Protocol

- African Intergovernmental Organizations

- Individuals and Non Governmental Organizations provided that the State party against which they act has made a declaration in terms of Article 34(6) of the Protocol allowing such applications.

4.2 Substantive jurisdiction

Article 3 provides that the Court has jurisdiction over all cases and disputes submitted to it on the interpretation and application of the Charter, the Protocol and any other relevant human rights instrument ratified by the concerned States. It follows therefore that the scope of the Court’s jurisdiction is very broad.

4.3 Admissibility of an application

The Charter provides for the following conditions:

- The identity of the applicant must be disclosed

- The application should be compatible with the Constitutive Act of the African Union and the Charter

- No disparaging language must be used

- The application must not be exclusively based on media reports

- It should be filed after exhausting local remedies, if any, unless it is obvious that this procedure is unduly prolonged

- It must be filed within a reasonable time

- It should not be about cases already settled within the UN or AU framework

4.4 Possibility of an amicable settlement

In terms of Article 9, the Court can, in contentious cases, promote amicable settlement in accordance with provisions of the Charter.

4.5 Consideration of the merits

Where the Court finds that it has jurisdiction and that the application is admissible, then it has to consider the merits of the case.

4.6 Findings/Judgment

The Court can issue appropriate orders to remedy a human rights violation, including the payment of fair compensation or reparation.

In cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable harm to persons, the Court can adopt provisional measures as necessary.

The Court gives its judgment within ninety (90) days of having completed its deliberations. Its judgment is final and not subject to appeal.

However, in light of new evidence, which was not within the knowledge of a party at the time the judgment was delivered, a party may apply for review of the judgment. This application must be within six months after that party acquired knowledge of the evidence discovered.

The Court may also interpret its own decision.

4.7 Execution of Judgment

In terms of Articles 29 and 30 of the Protocol, there shall be notification of the judgment to all relevant parties, and the State Parties undertake to comply with the judgment of the Court within the stipulated time and to guarantee its execution. In this regard, the Court shall notify the Executive Council of the AU in order for it to monitor execution.

5. The role of the Court in advisory matters

5.1 Entities that may seek an advisory opinion

In accordance with Article 4 of its Protocol, the Court may provide an opinion at the request of:

- Member State of the African Union

- The African Union

- Any organ of the African Union

- Any African Organization recognized by the African Union.

5.2 Subject matter of the request

The opinion may be on any legal matter relating to the Charter or any other relevant human rights instrument, provided that the subject matter of the opinion is not related to a matter being examined by the Commission.

The request must specify the provisions of the Charter or instrument in respect of which the opinion is sought, the circumstances giving rise to the request as well as the names and addresses of the parties and their representatives.

5.3 The advisory opinion

Like a judgment, the advisory opinion shall be accompanied by reasons, and will normally be delivered in open Court.

But, it will not be legally binding.

6. Applicable law

Pursuant to Article 7 of its Protocol, the Court shall apply the provisions of the Charter and any other relevant human rights instruments ratified by the States concerned (see also Articles 3 and 4 of the Protocol mentioned above)

The Court therefore has a very wide legal framework within which to discharge its mandate.

7. Overview of the achievements of the Court

From 2006 to 2008, the Court mainly worked on its operationnalization from the administrative perspective. It dealt with issues like: budget; Registry structure; recruitment of staff, the seat of the Court; the Interim Rules of the Court, etc. By the end of 2008, the Court was ready to receive and hear the first cases.

Unfortunately, from 2008 to 2010, partly because of lack of awareness, the Court received only one case brought by an individual against Senegal (Yogogombaye case) in relation to the Hissein Habre matter. The Court found that it didn’t have jurisdiction to hear the case, because Senegal hadn’t made the declaration accepting the competence of the Court to hear cases brought by individuals or NGOs.

Fortunately, since the beginning of 2011, the Court has started receiving cases: 12 applications in contentious matters, and one request for an advisory opinion. It has already made decisions in 6 contentious matters.

Today, one can say that the Court has become operational, both from the administrative and judicial perspectives.

II. STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES AFFECTING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE COURT

Having set out the general overview of the Court, I shall now turn to the strengths and weaknesses which arise out of the portrait of the Court that I have drawn above. And this subject is very topical especially in view of the fact that the Court has started receiving cases.

1. Strengths

1.1 Strengths arising from the Court’s mission

As the sole judicial organ of the African Union, with power to deliver binding judgments, the Court’s mission of complementing and reinforcing the functions of the Commission in protecting human and peoples’ rights provides it with a unique opportunity to further develop the African human rights system through its jurisprudence. As no other institution in Africa has the same continental judicial function, the Court can make its mark by setting jurisprudential standards that no other body can possibly do.

1.2 Strengths stemming from the applicable law, and the Court’s jurisdiction

We have already observed from the overview of the Court that its jurisdiction and applicable law are very broad. This provides the Court with a wide toolkit to apply towards developing the African human rights system and jurisprudence and charting new grounds for human rights protection in Africa and internationally.

The other potential strength of the Court comes from its jurisdiction. First, within its contentious jurisdiction, it is vested with the power of attempting an amicable settlement between the parties. Secondly, it also has a broad advisory jurisdiction, which enables it to play a broader role than a traditional Court of Justice.

1.3 Strengths arising from the independence regime for Judges

Although the nominations for the office of Judge are made by States parties to the Protocol, Judges are elected in their personal capacity. Moreover, if the Judge is a national of any State which is a party to a case submitted to the court, that Judge shall not hear the case. Lastly, there is a strict incompatibility regime which avoids situations where some officials of the Executive or the Legislative at national level could be Judges of the Court at the same time.

1.4 Strengths arising from the current African human rights architecture

Being the first continental judicial body charged with the responsibility of ensuring that the provisions of the Charter are respected and observed places the Court at the apex of the African human rights architecture. This offers the Court the opportunity to strengthen this architecture.

1.5 Strengths stemming from the possible extension of the Court’sjurisdictionto deal with serious international crimes

If the AU Policy organs decide to adopt the proposals to extend the jurisdiction of the Court to cover serious international crimes this will be yet another opportunity for the Court to contribute to the development and consolidation of international criminal law and to establish a viable human rights culture on the African continent which takes into consideration the continent’s specificities.

2. Weaknesses

The paradox is that the very same institutional and structural framework that gives it strength is also the bedrock for the weaknesses that confront the Court.

2.1. Weaknesses arising from the Legal Framework

While the legal framework for the Court is very broad in terms of the applicable law and the scope of its jurisdiction, the very same legal framework has set up barriers that limit the functionality and effectiveness of the Court.

2.1.1. Ratification of the Protocol

There are only just under half of AU Member States, twenty six (26) in total, that are State Parties to the Court’s Protocol. These States are Algeria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Comoros, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Lesotho, Mali, Malawi, Mozambique, Mauritania, Mauritius, Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia and Uganda. New ratifications are also slow in coming. Just to illustrate, since 2008 to date, there has only been one additional ratification of the Protocol: by Congo.

The impact of this challenge is that the Court can only complement the Commission’s protection mandate of the rights guaranteed in the Charter in respect of only the 26 State Parties to the Protocol whereas the goal is to have universal ratification thereof so that the Court is able to exercise its human rights protective mandate for citizens from all AU Member States. Apart from the fact that this state of affairs limits the effectiveness of the Court by shutting out potential cases, it also limits the territorial jurisdiction of the Court.

2.1.2 Deposit of the Declaration allowing individuals and NGOs to access the Court.

There is limited direct access for individuals and NGOs because only five State Parties to the Court’s Protocol have deposited the declaration required under Article 34(6) thereof. These five are Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, Mali and Tanzania. The Court therefore finds itself in a paradoxical situation whereby it is a human rights Court to which access by individuals, who are the ones who experience human rights violations, is limited. The scope of the Court’s judicial protection of human rights will necessarily be limited and so will its jurisprudence. Already, the Court has had to dismiss a large number of the twelve (12) applications it received, precisely because they are from individuals against member states which have not made the declaration.

2.2. Weaknesses arising from the Court’s transitional nature

The transitional nature of the Court due to its merger with the Court of Justice of the African Union to form the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, and to the possible extension of its jurisdiction to include criminal matters makes institutional development and planning a challenge. The fluidity of the situation makes the Court’s stakeholders and partners unsure of the extent to which to support the Court and for what activities.

2.3 Lack of awareness about the Court

Related to the uncertainty about the Court by Member States, is the confusion or lack of awareness about the Court across the board. There are low levels of awareness as to the existence of the Court and its potential for addressing human rights violations. It is with this realization that the Court has embarked on an awareness raising strategy in different AU Member States targeting its publics therein and giving them information about the Court and how to access it.

2.4 The Status of the Court within the African Union Framework

Since the beginning, the Court has claimed to have within the African Union, the status and the position it deserves, as the unique continental judicial body. Although some progress has been made over the years, the perception within the African Union framework appears to still be that the Court is not one of the main pillars of the African Union governance structure.

2.5 Judges working on a part- time basis

Apart from the President, the Judges of the Court are part time, and reside and are fully employed in their respective countries. This means that they can only attend to the business of the Court once every three months over a period of two weeks. This can delay the decisions of the Court both in judicial and non- judicial matters, which affects the effectiveness of the Court.

2.6 The organizational structure of the Registry

The current structure of the Court’s Registry is inadequate. There are several posts key to the functioning of an international Court which are missing in the current Court Registry’s structure. For instance, there are no positions for Court reporters, transcribers, recorders and revisers and some departments such as archiving are left out. In addition, the Court has inadequate staff such as legal officers. The support services it needs are also inadequate mainly due to the combination of distinct departments which cannot be manned by one officer currently in place, for example, IT is lumped with information and communication, and library is tied to archiving.

In 2009, the Court submitted to the AU Policy Organs proposals for review of its Registry’s structure but these are yet to be considered. In its just concluded Nineteenth Ordinary Session held in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, the Executive Council of the AU directed that the relevant Committee of the Permanent Representatives’ Committee of the AU should consider the Court’s proposals on the revised structure of its Registry and submit its report thereon to it for consideration in January 2012 at its next Ordinary Session. The Court hopes this exercise will finally be completed.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, it is clear that while the Court has great opportunities to put Africa on the map in terms of the development of international human rights and international criminal law, the challenges it faces could hamper it in this regard. For its part, the Court has tried to overcome some of these challenges by initiating a promotional programme to raise awareness about its role with the objective of generating more ratifications and deposits of the declaration allowing individuals to access the Court as well as encouraging seizure. The Court has made submissions to the AU policy organs with regard to the structure of the registry. It is fair to say that the response from the policy organs has been encouraging. Together, all of us African stakeholders who have a vested interest in the effective functioning of the Court, will no doubt continue to work together and share ideas to remove the major stumbling blocks that confront the Court